Books

The first of several books to be written by John Serrano

New Release

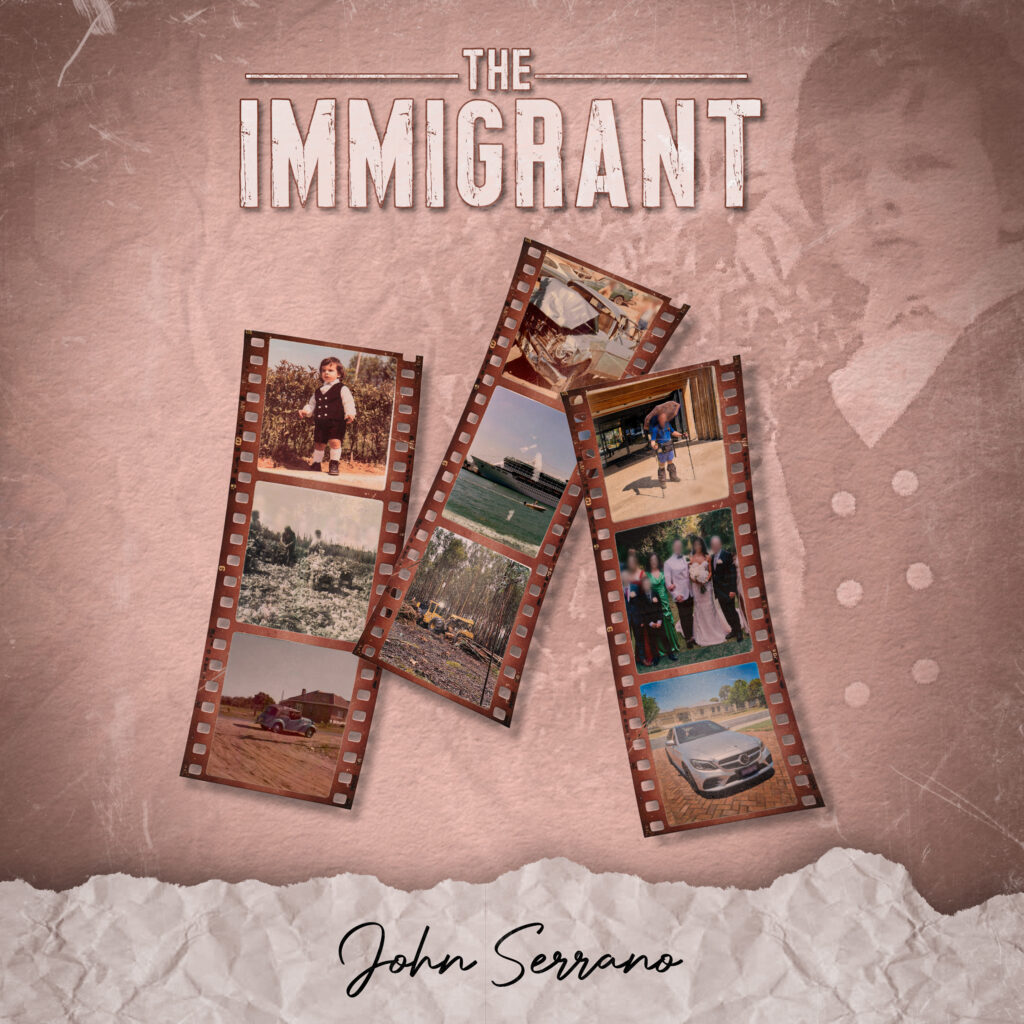

The Immigrant

Chapter 1. How I met my wife

I used up one of my lives that night when I turned off First Street onto the Ronald Reagan Freeway. I must have been very exhausted because, before I knew it, I fell asleep at the wheel. The sound of tires crunching against the sand near the roadside kerb jolted me awake. Just a foot more to the right and I would have slammed into a light pole. My heart pounded as I realized how close I had come to disaster. Instinctually, I rolled down the windows, letting the sharp night air shock me into full alertness. Then I floored it all the way home, forcing myself to stay awake with the sheer speed of the drive.

I decided then and there that I would not go out with Leah again: The drive was too long, and frankly, I wasn’t interested enough to risk my life over her.

The following night was a warm summer Saturday night full of possibilities. Lucas, Javi Pereira, and I started our night by hopping between the local bars, but nothing exciting was happening. So, we made our way to El Paraíso nightclub around 8:30 PM. We danced with a few regulars, then I spotted a table of girls I knew and decided to join them.

Camilla was there. She was a woman I had taken as my date to a 21st birthday party a few months prior. She was effortlessly charming. As her parents were still overseas, she had come out with her older sister. Their table was packed with her friends, all lively, laughing, full of energy. Instead of sitting with the guys, I pulled up a chair and joined them, sensing that this was where the real fun of the night would begin.

As I sat at the table, talking and laughing with the girls, a voice came from behind me.

“Hi, John.”

I turned, curious to see who had addressed me. It was Catalina a girl I had once taken out to lunch with plans to bring to the beach months ago. Back then, my intentions had been less than honorable, and I suspected she had been warned. Our last interaction hadn’t ended well. She had called me at work while I was in a training session, catching me off guard and embarrassing me in front of colleagues. I had been short and dismissive with her, and after that, we never spoke again.

So, I had to think twice when she came up behind me. Who was she, and what did she want?

“I saw you here and thought I’d come and say hello,” she said, fluttering her eyelashes at me.

“Hello,” I replied, keeping my tone neutral.

That’s when I noticed another girl standing a few steps behind her. Seizing the opportunity to shift the conversation, I asked, “Who’s your friend?”

“This is Paula,” Catalina said, gesturing toward her.

I raised an eyebrow. “Paula? That doesn’t sound very Spanish. What’s your real name?”

The girl’s expression darkened slightly. “Palomba,” she corrected, her tone laced with disdain.

“Oh,” I said casually, then turned back toward the table, dismissing them both without a second thought.

As they walked away toward the bar, a thought nagged at me. What’s wrong with you? A new girl walks into the club, and you don’t even give her a second look?

This was El Paraíso Nightclub or better known to us as the Spanish Nightclub. A new girl in the club was something you noticed because if she was any good, she wouldn’t stay single for long. Normally, I was always on the hunt, yet I had barely spared her a second look. That just wasn’t like me at all.

I made a point of turning around to get a better look as she walked away. Shoulder-length hair, a satin blouse flowing effortlessly over matching satin pants. Petite, but well-proportioned. Not much of an ass to speak of, but everything else was in the right place.

Not bad, I thought.

As the music began for the next dance bracket, I rose, scanning the room for a potential dance partner. Approaching the bar, I noticed the two girls standing there, looking lost and out of place. They seemed like fish out of water, unsure of what to do. Spotting an empty table nearby, I decided to be a gentleman and invited them to join me and my friends.

Catalina, being closest to the table, slid in first, clearly expecting me to sit beside her. Instead, I quickly guided Paula to the seat next to her and took the chair on the other side, placing Paula between us. Lucas and Javi settled into their spots across from us. As we exchanged small talk, Paula leaned in and whispered, “Who’s the creep in front of us?”

I stifled a laugh and murmured, “That’s my friend.”

She blinked, then simply said, “Oh,” and fell silent.

Suddenly, a voice called out from behind us, “Paula. What are you doing here?”

A young man in his mid-20s stood there, clearly familiar with her. She smiled warmly at him and said, “Hello! We’re just here to pick up Catalina’s sister.”

They exchanged a few more words and pleasantries, and eventually, he left. Throughout their interaction, I couldn’t help but wonder who this interjector was. When Paula turned back and saw me watching them, she smiled quietly, placed her hand gently on my leg, and reassured me, “Don’t worry; he’s only my butcher.”

I looked at her with quizzing eyes as if to say, “Why are you telling me this?” However, Her touch was comforting, and her words were meant to ease my curiosity. Somehow, in that small exchange, it was clear we both felt a connection neither of us wanted to ignore.

The music started up again, and I asked Paula to dance. She smiled and accepted. We swayed together through a few slow waltzes, the atmosphere buzzing with a quiet kind of electricity.

“Where do you work?” I asked as we moved.

“West 6th Street,” she replied.

I raised my brows. The busiest business district in town.

“Oh?” I said, intrigued. “So do I.”

She studied me curiously. “Which building site?” she asked, assuming I was a tradesman.

I chuckled softly. “No, I’m an accountant at one of the Big Eight firms.”

She seemed impressed. “I work for a law firm as a debt collector.”

We kept talking until the music stopped, and we returned to our seats. During the break, Paula and Catalina went to the restroom, leaving me behind with my friends. Unbeknownst to me, in the restroom their conversation went something like this:

Catalina: “I think he likes you.”

Paula: “Oh, don’t be silly. He likes you. I’m not interested.”

When they came back, the music started again, and I asked Paula for another dance.

“So, what’s your number?” I asked.

“I don’t have a telephone,” she said.

I stared at her in disbelief. “What? I don’t believe you. Everyone has a telephone nowadays.”

She laughed. “No, really. We have a payphone outside our house. If I ever need to call someone, I just go across the road and use it.”

“Fine, then, what’s your work number?”

She hesitated. “You’ll never remember it.”

“Try me.”

Reluctantly, she gave me the, then 7 digit number, 322 4522 and I went silent, repeating it over and over in my mind, committing it to memory.

Later, after our final dance, I walked Paula and Catalina to their car before heading to mine. As soon as I slid into the driver’s seat, my friends pounced.

“Did you get her number?”

“Quick, give me a pen!” I pleaded.

No one had one, and in the chaos of the car, I couldn’t find anything to write with. Desperate, I grabbed a match, struck it, and used the burnt end to scribble her number onto the back of the matchbox. A makeshift solution for an unforgettable night.

Up until that moment, I had kept a meticulous diary, documenting every adventure, every fleeting romance, every chapter of my teenage years. But after meeting Paula that fateful evening, something changed. Writing in my diary suddenly felt meaningless.

My last entry was about the night I dropped Leah home. After that I never picked up my pen again. Somehow, deep down, I knew, Paula and I were meant to be. And if I ever forgot, she would always be there to remind me of the memories we built together.

Chapter 2. A bit of history

Around the 1920s, a daring young man named Juan Roco Serrano embarked on a journey across the rugged Cantabrian Mountains in Northern Spain. His adventure led him to a quaint medieval town on the banks of the Ebre River, where he met a charming young lady named Concetta. They fell in love, married, and settled in the picturesque town of Mora D’Ebre, where they raised four children. The third of their children was my father, Rolando Serrano.

Abuelo Roco was a man of boundless energy and resourcefulness. Hailing from a small town near Bilbao in the province of Vizcaya, his proximity to the bustling port city of Bilbao seemed to imbue him with a natural talent for trade. He quickly established a thriving merchandise business, selling goods door to door, setting up market stalls in town squares and bartering with farmers for their produce in exchange for his wares. From his horse and cart, he traded plates, glasses, needles and combs, returning home laden with sacks of wheat or corn, bottles of oil, or fresh vegetables to sell the next day in another town square.

His business flourished allowing him to purchase a grand 18th-century house from the local nuns, complete with stables, a cellar, and a barn to store his goods. Ever the strategist, he divided the spacious home into four small apartments: one for himself and the rest for his three sons and their future families. His only daughter, newly married, settled in a nearby town.

Roco’s prosperity extended beyond his home. He was the first person in town to own a car, though he never learned to drive and instead employed a personal driver. He acquired vast stretches of land, often sealing deals with a simple handshake, avoiding the bureaucratic hassle of paying stamp duty to transfer the titles into his own name. Instead, he would simply tuck the physical title deeds to the lands he acquired inside a hole in his bedroom wall.

Fortune, however, is fickle. During the Spanish Civil War, Roco fought under Franco’s regime and was left partially blind in one eye from his injuries. After the war, his business flourished once more. But never one to sit still, one day he took it upon himself to “requisition” some railway steel tracks abandoned behind the local station and sell them for scrap. In a small town like Mora D’Ebre, it didn’t take long for fingers to point his way. He spent eight months behind bars, courtesy of the policía. Yet, despite this, he remained a well-known and respected figure, known by all in the area as Don Roco, “el buhonero” meaning the peddler.

As a testament to his fame , decades later, when I was around fifty, I visited a Spanish client in Malibu who had emigrated from Catalonia in his twenties. His elderly mother, now living with him, was thrilled to meet someone from her hometown. When she asked for my family name, it didn’t ring a bell. But when I mentioned that I was the grandson of Don Roco, her face lit up with recognition.

“Don Roco, el buhonero!” she exclaimed. “I remember him well. My father owned the cantina by the railway crossing just out of town. Don Roco would always stop by for lunch and order a quart of red wine with his meal.”

That was my grandfather. A man who lived boldly, did business on his own terms and enjoyed a glass( or several) of wine. His love of wine and relentless smoking eventually caught up with him and he passed in his early seventies from heart disease. But his legacy of grit and determination runs deep in our family’s DNA.

My father, Rolando, grew up in a time of abundance, even as the shadow of the Spanish Civil War loomed over his town. He was never one for academics. School was more of a nuisance than a necessity. He skipped classes so often that he repeated third grade three times before his father finally decided that formal education was a lost cause. Instead, he was ushered into the family business, though his true passion lay elsewhere. He was endlessly fascinated by motors, always eager to tinker and fix whatever he could get his hands on. When the time came for his mandatory 12-month military service, Rolando’s natural talent with machines did not go unnoticed. He was assigned to the motor vehicle workshop, where he learned to drive and repair trucks, a skill that would serve him well in the years to come.

Rolando was a jovial, happy person, always singing while working in his market garden or fixing a friend’s broken-down lawn mower. He was quick to help anyone in need, never hesitating to lend a hand. But his temper was just as quick as his generosity. He could erupt like a storm, his fury striking with little warning, only to dissipate moments later as if it had never happened. He had many friends and loved to share a cup of coffee, a beer, or a glass of wine with them. He loved to travel, meet people, get involved and he was not afraid to take risks. Whether it was helping to look after his many grandchildren with his wife, fishing with his grandchildren, working at his job, or simply playing cards with his friends, he always put his heart and soul into anything he committed to and he did it with passion. To him, the glass wasn’t just half full, it was overflowing.

My mother, Gabriela, was no stranger to hardship. Like so many others, she endured the brutal realities of the Spanish Civil War, which took her mother when tuberculosis struck. Had there been access to penicillin or any proper medicine, she might have survived. Left behind when her father moved to Barcelona for work, Gabriela was raised by her aunt Netta. Years passed before her brother Alvaro could join their father, partially reuniting the family.

After her mother’s death, Gabriela’s life became even more complicated. Pressured by his children, her father remarried, but Gabriela and her stepmother clashed from the start. This drove a wedge between her and her father that never fully healed. These struggles shaped her into an unyielding woman who never hesitated to speak her mind. Yet beneath her tough exterior was a heart brimming with devotion. To her children, she was a pillar of strength, her love unwavering and unconditional.

Soon after moving into their new home, 15-year-old Rolando met Gabriela, who lived just 400 yards away down a dirt path leading to the old flour mill. The moment he saw the 13-year-old girl, he was smitten and boldly declared, “I will marry you one day.” Gabriela, still mourning her mother, rejected his advances. But Rolando was persistent. When she turned 18, he proposed, and she finally accepted.

Life in the post-war years was harsh, especially in the countryside. My mother often spoke of their struggles. They had so little in those early days that my father couldn’t even afford an engagement ring. Every penny went toward their wedding bands, symbols of a love that would endure every hardship.

They married in January 1950, in a small church in Mora D’Ebre, surrounded by family and friends. It was the beginning of a lifelong partnership that lasted 57 years, until my father’s passing in 2007.

After their wedding, my parents moved into the modest two-room apartment in my grandfather’s building, with a single room downstairs and a single bedroom upstairs. The downstairs space served as their kitchen and living area, warmed by a wooden fireplace. A benchtop held a two-burner propane stove and the floors were made of brick. A steep, ladder-like staircase led to the single upstairs bedroom, where a small balcony window let in slivers of sunlight. There was no indoor plumbing and the stables doubled as their toilet. Water had to be collected daily from the town fountain, carried home in my mother’s conca, a deep copper pot balanced skilfully on her head. Baths were a rare luxury, with water heated on the stove and poured into a small metal tub. Entertainment was simple, there was no television, but they had love, laughter and a roof over their heads. What more did they need?

My father, Rolando, followed in his father’s footsteps as a peddler selling pots and pans in the various town squares along with his father and younger brother. Soon after, he teamed up with his cousin Salvador, who was the same age and together they continued the family trade, selling merchandise door to door and setting up stalls in the various bustling town squares.

Just a year after their wedding, in January 1951, my parents welcomed their firstborn, a daughter Consuela, named after my mother’s mother. Their tiny upstairs bedroom now housed a crib, a chest of drawers, and their matrimonial bed. Space was tight, but love filled every corner and they made it work, just as they always did.

Four years later, on a bitterly cold winter morning, my mother, heavily pregnant with their second child, felt a little off. Concerned, Rolando asked if the baby was on its way. Gabriela, ever practical and not wanting him to miss work, waved off his concerns. “Don’t worry, it’s still too soon. Go out and earn some money as today is a fine day. Who knows whether it will rain or snow later in the week?”

Trusting her words, Rolando set off on his selling rounds, riding his Lambretta alongside his cousin Salvador. Hours later, as he returned home, his younger brother, Sancho, but known as Platino, came running up grinning from ear to ear, shouting triumphantly, “It’s a boy!”

And that was how I, Juan—better known as Juanito—entered the world, born around midday in my parents’ matrimonial bed on Calle Fondón in Mora la Nova. Their already cramped bedroom now had to accommodate not just my parents bed but also a small bed for my sister and a crib for me.

Calle Fondón took its name from the Fountain of Fondón, just a hundred yards down the road from our house. For centuries, this fountain had been the lifeblood of the town, fed by a natural spring that bubbled up from the foot of the hill. In medieval times, ceramic tiles had been laid to guide the water into two metal pipes which poured from the mouths of intricately carved stone faces into a pair of large stone basins. The left basin was reserved for travelers passing along the road to water their thirsty horses and oxen, while the right was where the town’s women gathered to wash clothes and collect drinking water.

The fountain was more than just a water source. It was a social hub, a place where the town’s women gathered daily to collect their water, chatting and laughing as they balanced their concas filled with water effortlessly atop their heads as they carried them home. It was where gossip flowed as freely as the water. Where men watering their animals would linger just a little longer to chat with the women washing clothes. If only those fountain heads could speak, imagine what a treasure trove of secrets and gossip they could reveal!

Chapter 3. The current state of affairs

I am an ordinary man who recently turned 70. After several years of retirement, I now spend my days in a comfortable home near the beach, enjoying the life I worked so hard to build. My career as a Certified Public Accountant (CPA) spanned many years, first as an employee and later as the owner of my own business. Over the years, I have accumulated enough wealth to classify me as middle class, not extravagant, but comfortable. My wife and I own our four-bedroom, two-bathroom house outright and our garage houses two near-new Mercedes, an SUV for our countryside escapes and a sleek sedan for city life, each a symbol of our well-earned comfort.

Several years ago, having reached close to retirement age, I made the decision to sell my accountancy practice. It was a defining moment where one chapter closed and another opened, filled with freedom and possibility. Today, we live as self-funded retirees, sustained by property holdings, a substantial share portfolio and prudent savings. Our wealth generates a steady stream of passive income from rents, dividends, and interest, allowing us to maintain our lifestyle without eroding our capital or depending on government aid.

I wasn’t born with a silver spoon in my mouth, nor did I achieve financial success through inheritance. My achievements are the fruits of sacrifice, persistence, and an unwavering belief in my own abilities. Now, I know what you’re thinking, here’s another old fart reminiscing about the good old days and how things were tougher in his day. You’ve heard it all before. This just happens to be my story

This story could have been written about a Mexican crossing the border in search of opportunity, a Moroccan building a life in France, or a Chinese immigrant finding work in Japan. It could easily be the story of an Anglo-Indian making a home in Saudi Arabia or a Malay striving for success in Singapore. But this story is uniquely mine. The tale of John Serrano a U.S. citizen of Spanish origins, a baby boomer born to working-class parents who migrated to the land of opportunity when he was very young.

Many people, whether by choice or circumstance, settle into a routine existence, predictable, safe, and unremarkable. I’ve never believed I belonged in that category. I’ve always been an optimist, convinced that life is meant to be lived fully, every single day.

When I was 24, newly married and eager to advance my career as a newly qualified accountant, my father-in-law offered what he thought was sound advice: “Why don’t you get a job with the government? With your degree, you could earn a good salary and have the security of never being unemployed. Government workers always get paid and their employer will never go broke. Eventually, you will climb up the ladder as other bosses retire, and one day you will retire with a handsome pension. You will also have all the benefits that come with a government job.”

It was practical advice, the kind many would have jumped at without hesitation. But to me, it felt like a slow suffocation. I hadn’t endured sleepless nights and long hours of study just to punch a clock and wait decades for a promotion. The idea of answering to someone else for the rest of my career, shackled by hierarchy and bureaucracy, was unbearable. I yearned for autonomy, for the thrill of forging my own path. I wanted my success, or failure, to rest solely on my own shoulders. Security was appealing, but adventure, ambition, and the promise of something greater burned brighter in my heart.

I wanted to be my own boss one day and to have my own business and be answerable to no one. If I succeeded, it would be due to my efforts alone. I was not about to live a mundane life simply because it was “safe.” I had already experienced enough to know that the ordinary life lived by most people was not for me. I wanted more out of life and I was not going to sit around and wait for it to come to me. I was going to go for it.

Life can either be a roller coaster ride or a merry-go-round, always going around in circles with the horse going up and down to give you a little bit of excitement. Many people go through life on the merry-go-round, always doing the same things, never taking a chance, always playing it safe. A roller coaster, on the other hand, first takes you up a steady climb to the top of the hill, then comes the breakneck speed down, the 360-degree loop, and the dizzy spinning around before reaching the end of the ride. I have always preferred living my life like on a roller coaster.

As I approach the final chapters of my life, I reflect on the words of Mussolini: “It is better to live one day as a lion than a hundred years as a sheep.” To me, life was never meant to be lived in a rut, because, as the saying goes, the only difference between a rut and a grave is that a rut has the ends kicked out.

Purchase the book if you want to read more.